How the Finance Bill 2025 Could Lower Net Salaries in Kenya

Section 17 of the Finance Bill 2025 proposes to insert a new clause into the Income Tax Act (Cap. 470). The clause would require that “an employer shall, before computing the tax deductible under subsection (1), grant an employee all applicable deductions, reliefs and exemptions provided under this Act.”

The referenced subsection (1) falls under Section 37 of the Income Tax Act (last revised in 2021), which currently compels employers to withhold and remit tax from employees’ emoluments “in such amount and manner as may be prescribed.”

Under the proposed amendment, the Finance Bill 2025 proposes a subtle but significant amendment to the Income Tax Act, requiring employers to apply all applicable deductions, reliefs and exemptions prior to calculating Pay as You Earn (PAYE). While it may appear that this has always been the standard practice, the critical change lies in the sequencing: personal relief, which has traditionally been deducted after computing the tax liability, would now be treated as a pre-tax adjustment.

The Income Tax Act outlines three key types of personal relief: general, personal, and insurance. These are provided for under Sections 29, 30, and 31, as well as Part V of the Income Tax Act so these will definitely be included. This proposed and obscure amendment carries two key implications for the taxpayer, further complexity in the income tax system and potential reduction in the net income.

Tax policy design should strive to uphold the principles of clarity, equity, and efficiency, yet this proposal undermines all three.

First, there is a lack of clarity on the rationale for overturning a long-standing method of computing income tax or how this change affects the personal relief of Ksh 2,400 for which each taxpayer is eligible. The Finance Bill does not explicitly address whether personal relief will continue to be applied after tax is computed or be treated only as a deduction before calculating taxable income or both ways, an important distinction that has implications not only for how much tax is ultimately payable, but also for what the average tax rate will be.

Secondly, Part V of the Income Tax Act currently provides that personal relief is to be set off against tax payable by a resident individual for a year of income, provided they have furnished an income tax return. Specifically, it states that the personal relief shall be applied against the tax payable, at the rate and within the limits specified in Head A of the Third Schedule. This provision has not been amended in the Finance Bill.

This creates a legal and interpretive inconsistency. On one hand, the Finance Bill proposes that all applicable deductions, reliefs, and exemptions be granted before calculating PAYE. On the other hand, the unchanged provision of the Act implies that personal relief should come after tax has been determined. If both provisions are read together, it could lead to confusion or even the application of personal relief twice, once as a deduction from gross income and again as an offset against tax payable.

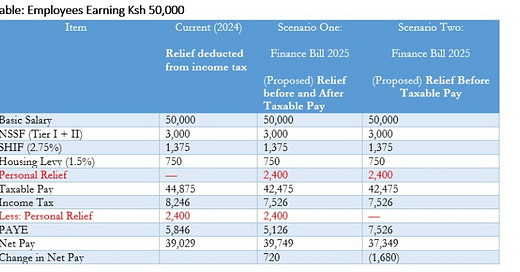

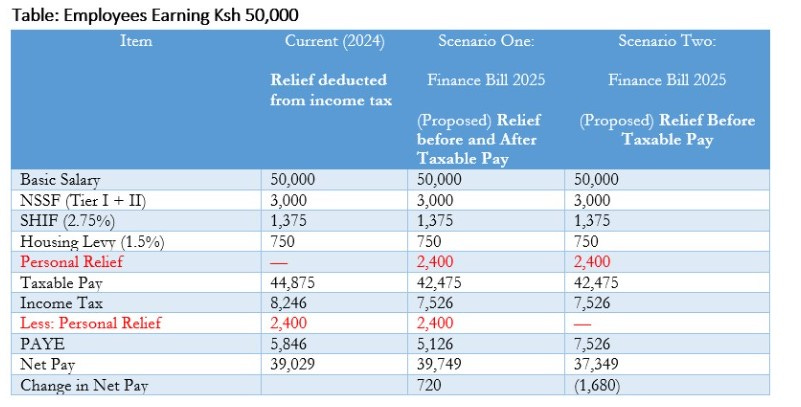

For illustrative purposes, we modelled outcomes for a citizen earning Ksh 50,000. In the current regime, tax is assessed on the taxable income, and a fixed personal relief of Ksh 2,400 is applied against the PAYE due, effectively reducing the employee’s final tax liability. This is important as it shows how proposed tax reforms behave in practise.

If the personal relief of Ksh 2,400 is applied both as a deduction before computing taxable income and again after as an offset against the tax payable, the individual’s net income would increase by Ksh 720 as shown in Scenario One below.

However, if the relief is applied only as a deduction before computing taxable income, contrary to the existing law which requires it to be offset against tax payable, the reduction in net income would be more significant, amounting to Ksh 1,680 as shown in Scenario Two. While this lowers the taxable base marginally, it eliminates the subsequent Ksh 2,400 reductions on PAYE. As a result, the PAYE payable increases, leading to a lower net income across all salary bands. Despite appearing taxpayer-friendly on the surface, the amendment reduces disposable income for employees and erodes purchasing power, particularly for lower and middle-income earners.

This is especially significant given the political rhetoric surrounding the 2025 Finance Bill, which claims that there are no new tax increases. However, as this computation and analysis will demonstrate, the effective tax burden on salaried workers will rise when this change is affected. This suggests that, while no new tax rates may have been introduced, the structure has been quietly altered in a way that extracts more revenue, contradicting the government’s public stance.

Alternatively, if the intention is to apply this new rule only to other reliefs, and not personal relief, then the Bill ought to clearly exclude personal relief from this change. As currently drafted, the law is ambiguous and opens room for multiple interpretations, which may undermine tax certainty and proper implementation.

For Scenario Two, there is both an efficiency and equity question. Efficiency is compromised, while, governments have a legitimate need to raise revenue, they should do so with minimal distortion to economic behaviour. By reducing employees’ disposable income, this proposal risks discouraging savings. Finally, equity is eroded, especially for low-income earners who rely heavily on the Ksh 2,400 monthly personal relief if the law is applied based on Scenario Two. For many, this relief offsets 29% or more of their tax liability. Diluting its impact disproportionately increases the tax burden on the most vulnerable.

Conclusion

The proposed amendment in the Finance Bill 2025 should be made clear, especially if the goal is to support salaried employees who are already grappling with high statutory deductions and a rising cost of living. By altering the sequence of how personal relief is applied, from a pre-tax credit to a post-tax deduction, the change risks reducing take-home pay, particularly for lower and middle-income earners who depend heavily on this relief to offset their tax liability. As illustrated, depending on how the law is interpreted, this shift could either modestly increase or significantly reduce net income.

Remember, this adjustment comes at a time when employees are already preparing for further reductions in net pay, with NSSF contributions set to rise again in the fourth year of implementation. Layering this change onto other recent and upcoming deductions undermines the very purpose of tax reliefs, providing financial cushioning. Instead, it may amount to taxation by stealth, where policy adjustments extract more from taxpayers without explicitly raising rates. This not only strains household budgets but also erodes public trust in taxation policy, both in Parliament’s legislative intent and in the transparency of tax administration authorities. The law should be clear, a standard this amendment currently fails to meet.

By Fiona Okadia